The Japanese Gift Culture - Giving and Receiving

Gifts are very important in Japan. From the small tissue pack at the store entrance to the vacation souvenir and the sake bottle as a gift – you will encounter them sooner or later as a traveler. In Japan, there are approximately over 50 occasions to give someone a gift. Where do these rituals come from, how do you follow them correctly, and what can we learn from them?

People and gods

Gifts in Japan have a religious origin in Shintoism, one of the two predominant religions in Japan. While in Christianity giving is valued higher than receiving, here gifts are exchanged with the gods for favors. Naorai is, for example, called the sharing of food with gods: In ancient Japan, offerings in the form of food were made to the gods, which were then shared together. Hence, for example, the money gifts to children on New Year, Otoshidama, which originally were also such religious offerings. In the past, children received Mochi – rice cakes symbolizing the divine soul.

So, the offerings were a gift to the gods, which they returned so that people could share it. This principle of giving and receiving, hidden behind the term Giri, is deeply rooted in the Japanese psyche to this day. The way it is followed can even reveal a person's character.

Give and take

The concept of Giri dictates that a gift should always be reciprocated. This is not just a friendly gesture: especially in rural areas, one was always dependent on the help of others. If you did not assist your neighbors materially and offer them appropriate gifts on certain occasions, you could not expect support yourself in times of need. Even in cities, mutual attentiveness served as a kind of social security. Today, favors and services are still reciprocated through small gifts, such as an elaborate treatment by a doctor.

However, gifts in ancient Japan had not only material but also spiritual benefits. According to Shinto belief, when someone was sick, they needed positive energy in the form of usually edible gifts from healthy people to recover faster. According to the Japanese calendar, there are also years that are considered particularly unlucky (Yakudoshi): for children, for example, three, five, and seven years old. Thus, the ritual was born that children should go from door to door at the age of seven and ask for food. This is, by the way, the only exception to reciprocity: accepting gifts from the sick or people in the "bad" age would bring misfortune and should therefore be avoided. Today, three-, five-, and seven-year-old children are instead dressed in traditional clothing on November 15 and taken to shrines to pray and make offerings to the gods for another happy and healthy year.

Giving preserves harmony

Almost half of all gifts in Japan are of a formal nature and serve to maintain social relationships and harmony – called Wa in Japanese. In the professional realm, gifts are indispensable, especially for business clients.

One of the most significant occasions for giving gifts in Japan is New Year, preferably with New Year cards known as Nengajo. Two other major gift-giving days of the year involve thinking of relatives, superiors, such as bosses, clients, teachers, and doctors: Ochūgen, the mid-year gift in July, during the Buddhist Bon holiday to honor the deceased, and Oseibo in December. Although Oseibo gifts are usually presented by December 20, they have nothing to do with Christmas. Rather, they are meant to express gratitude to superiors for their kindness throughout the past year. People typically spend between 3000 and 5000 yen (approximately 25 to 40 euros) on these gifts. Gifts on these occasions are usually practical in nature: for example, salad oil, food containers, and drinks are items that everyone can use.

Among friends and colleagues in Japan, it is customary to buy small souvenirs when traveling. Local sweets or small figurines are very popular choices. That's why you often see stores in Japan that specifically offer such souvenirs, called Omiyage. You can find items such as Kokeshi, traditional intricately painted Japanese wooden dolls, which have been a popular choice for hundreds of years – especially as a auspicious gift for children.

No celebration without a gift - the gift culture of Japan

There are over 30 private occasions and ceremonies in Japan where one receives gifts. For instance, during births, weddings, graduations, and funerals, families receive gifts from relatives, friends, and acquaintances. A traditional gift for weddings, for example, is high-quality lacquerware. However, even this does not go without reciprocation: the family must return the favor on the next occasion, such as bringing back a gift from their honeymoon. Therefore, it is crucial in Japan to make the price of a gift clear: this way, the recipient knows how much they should return. Since a gift obligates the recipient to reciprocate and places a burden on them, the gift is chosen not to be too expensive.

On Japanese Valentine's Day, only men receive gifts, usually chocolates. In the office, the quantity and quality of the sweets can indicate how popular they are among their female colleagues. They must reciprocate on "White Day," which takes place one month later on March 14th.

When invited to someone's home in Japan – a rare and very friendly gesture – one should always bring a gift. While presenting the gift, it is common to modestly state that it is just a small token and often reveal, unlike in some other cultures, what is inside. Also, it's advisable to wait until you are alone with the person before presenting the gift unless you have thought of everyone present.

When receiving a gift, it is considered polite to open it only when prompted or after the giver has left. It's also customary to politely decline the gift once or twice before accepting it, expressing that it is too much.

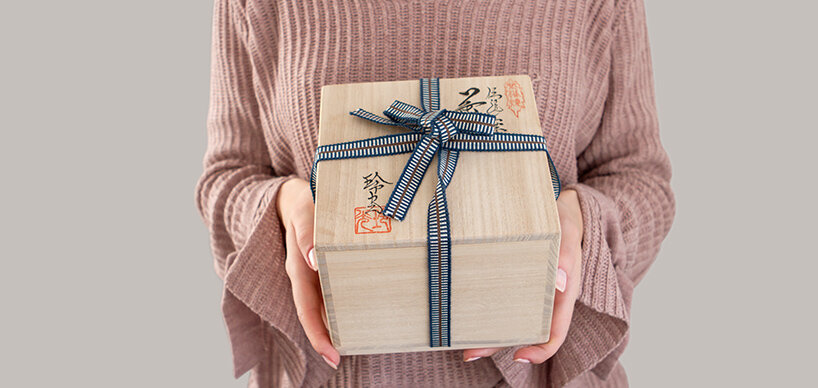

The right packaging for every occasion

That a gift must be beautifully wrapped goes without saying. In Japan, it signifies sincerity and appreciation, showcasing the effort put into the gift. Additionally, the color of the wrapping plays an important role in its significance: Pink is a positive and popular color, as are yellow, orange, and green. Blue is considered feminine, while noble purple symbolizes prosperity. Red is associated with strong emotions but is often used in funeral invitations and should thus be avoided for gift wraps. White should be avoided as it can be ambiguous, representing purity or death and rebirth, while black is generally an unfortunate color. The combination of red and white is a fortunate, powerful combination, whereas red and black together symbolize sexuality.

If giving money in Japan, as is often customary at major celebrations, it must be enclosed in an envelope. For Oseibo and Ochūgen, the packaging is particularly traditional: The occasion and the giver's name are typically written above and below the gift ribbon. Often, the original packaging from the store where the gift was purchased is used, allowing the recipient to immediately recognize the origin and value of the gift. However, it becomes truly traditional with Japanese Furoshiki cloths. Furoshiki has been popular for hundreds of years as a wrapping method: It protects the contents and offers another precious element that can be reused in various ways. Similarly, Tsutsumi ("packages") with special, elegant paper are used. An example of this is Chiyogami – Japanese paper that is not cut but instead folded almost in an origami style. Asymmetry and an odd number of folds are considered more aesthetic and lucky in Japan.

Gifts from the heart

However, strict and regulated gift-giving is only used in formal contexts. Relationships within family and among friends are called Ninjō and involve much more personal gifts. Ninjō roughly translates to "human feelings" and implies that gifts are given not out of obligation but from the heart. If one wishes to strengthen a bond with someone, a small token of attention can possibly turn an acquaintance into a friendship. Corresponding gifts for birthdays and similar occasions are a relatively modern phenomenon.

Currently, the "empty," formal style of gift-giving is criticized, especially by young Japanese who see little intrinsic value in it. According to their perspective, not much attention is given to the taste and personality of the recipient in this type of giving. This is also reflected in the tendency to send gifts rather than presenting them in person. Traditional concepts, communal motives, and the utility of such gifts are now being questioned.

Nevertheless, Japan, with its gift-giving culture, remains a society that places great importance on interpersonal relationships. Despite, and perhaps because of, the more pronounced individualism in other cultures, it's worth occasionally showing our loved ones that they are important to us – especially during this most significant gift-giving season. We wish you a contemplative and enchanting holiday season.

-from-the-yakiyaki-grill-pan.jpg)